There was clear joy on his fresh young face as a rider in the 1980’s, living his childhood dream by cycling in the Tour de France and doing so along his friend and countryman Stephen Roche. Then within a year he was dropping out of the same race due to ‘low morale’ and hiding his face from intrusive camera’s on the team bus.

In between he experienced the high of performance enhancing drugs which he described in the documentary as enabling him to clear a metal fence by three feet and feeling no pain in getting through another day on the bike.

When Kimmage called time on his professional career he did not go quietly. His ability for expression and explanation was turned on the sport which he knew at the time to be responsible not only for some of the most inspiring feats but also for the deaths of around 20 young cyclists ‘whose blood turned to treacle at night’ as a result of the EPO drugs they were being given.

Never about winning

The drugs at the time were never about winning the race, they enabled you to finish each day and then get back on the bike for the next day.

His was the first inside story that exposed systemic drug taking and it has cost him a lot over the last 24 years.

The documentary followed his return to the Tour de France last year, the first one after the full exposure of Lance Armstrong who Kimmage had hounded and harried, at great personal cost, since the first questions were asked about his remarkable seven consecutive Tour wins.

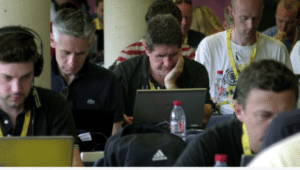

It was not an easy ride at all. Many fellow journalists were less than enamoured of his contention that not enough was done from those who should be questioning the sport and it’s teams. He walked through the press tents and into interview rooms with the air of a man who did not really want to be there.

Conflict

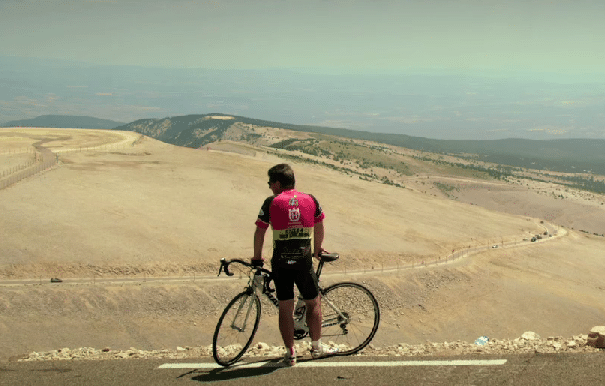

It looked as though he wanted to believe in last year’s runaway winner Chris Froome from Sky, and yet in his eyes you saw a sense of disbelief in the ability to do what he did on Mont Ventoux. This was the mountain on which Tom Simpson had died, largely from being pushed too hard on performance ending drugs. Now it was the scene for Froome killing off the opposition with a ride and subsequent recovery that looked too good to be true.

Froome was clearly upset that his moment of greatest triumph was greeted only with questions of drugs, not with the achievement itself. This is the price that those who followed Armstrong have to pay if Cycling is to recover its place in the hearts of those who once were its greatest advocates.

Two years ago I wrote a piece about why I wanted to erase the memory of Lance Armstrong, to forget his sullied triumphs, to wash away the rain that fell when I took my own kids to see a ‘hero’ of sport in the flesh at Bantry as part of his riding in the Tour of Ireland.

I felt the same as Kimmage watching last year’s Tour. I so wanted to believe but it just looked too good to be true.

The introduction of blood passports in cycling has moved it to the fore in terms of detection, and there were no positive tests at this year’s Tour, unlike the Commonwealth Game for example.

Betrayed

Yet because cycling has betrayed its fans so deeply in the past we will still take time to believe.

The unease that many feel with wanting to celebrate the achievement of Nibali, Kittell, Roche and Martin is still tempered by having been made fools of in the past. Most of us live that in front of the TV screen. Paul Kimmage does so on the screen.

I had the pleasure to meet him last year at an event organised by the Irish Sports Council. He is as he appears on camera, a man who knows he can write and write well about sport; a man who remains angry at those who threatened to destroy the sport he loved as a child and indeed his own career; a man who should really walk away from this one sport among many but who is continually drawn back.

It was not an easy film to watch. But sometimes those are the ones that are most important. And if Kimmage’s continual questioning helps bring cycling to a point where it is healthy, drug free and the real embodiment of what the human body is capable of, then it will have been worth it.

I hope he feels the same.